Protos - own your digital identity and data by self-hosting

Overview

Protos’s mission is to empower individuals and small organisations to establish or reclaim their digital sovereignty by building a [self-hosting](#self-hosting-a-way-to-decentralize-the-internet-and-attain-digital-sovereignty) platform for Internet applications and by promoting the formation of an ecosystem of applications around it. By enabling non-technical people to self-host, Protos aims to counteract the powerful trend in Internet centralisation and preserve the qualities of the Internet that make it such a powerful catalyst for innovation and free exchange of ideas.

What is digital sovereignty?

In the context of this text, “digital sovereignty” refers to the digital liberty and independence of an individual, as opposed to a country or geographical location, and it is embodied by the following principles:

- Individuals have full control over their digital identities, without being dependent on 3rd parties

- Data generated by an individual is owned by that individual, and only they should have the ability to choose what data and how much of it will be shared with other parties

Digital identity, and the data it accumulates over its lifetime are the basis of the digital self, being roughly equivalent to the physical identity and memories of an individual. If the reader agrees with this rough analogy, then, it stands to reason that digital identity is a concept worth exploring, especially in a world where people are increasingly dependent on their digital devices and the Internet.

Why is digital sovereignty important?

The internet is one of the most important human creations, and it has changed how our species communicate. Its open nature has created a level playing field in terms of access to information, and freedom of speech; giving people across the world the power of knowledge, and the ability to challenge oppressive authoritarian structures. Clearly, it is worth protecting the openness of the Internet and the unencumbered way people access it, and its centralisation threatens those characteristics that make it so revolutionary. It is time to reclaim our digital sovereignty and explore alternative approaches to using the Internet, approaches that can reverse the feudalistic tendencies eroding the principles that the Internet was built upon.

Is there a way to achieve digital sovereignty for an individual through a grassroots movement without relying on the existing power meta structures? Protos will focus on self-hosting, a promising approach to using Internet applications which is discussed in more detail in the upcoming sections.

What are the goals of Protos?

Protos will pursue its ideology by setting the following goals:

- create a self-hosting platform that kickstarts the community by demonstrating a software implementation that is easy to use for the end user, but also promotes an application runtime model that is geared towards automatic management.

- foster a community of like-minded individuals and organisations that believe in the ethos of decentralisation, and can come together and help build the ecosystem required for self-hosting to succeed.

- create and run an application store which will, on one side, allow users to download free or paid applications, and on the other, allow developers or application creators to reach an audience and potentially monetise their creations.

- create or leverage an existing cryptographic identity model that allows individuals or organisations to retain control over their online identities without relying on 3rd parties.

- long term, incentivise hardware manufacturers to create specialised hardware for the purpose of self-hosting; hardware that can be used from home, office or a data center.

At the time of writing, self-hosting is a small niche attractive only to IT hobbyists that have the necessary skills and the time to approach it. Protos’s meta goal is to change that by dramatically lowering the barrier to entry, and opening self-hosting to the average user, protecting digital sovereignty in the process.

Why is Protos needed?

Computing has become ubiquitous, and the internet has fundamentally changed how people interact. People have, on a daily basis, come to rely on their smartphones and computers which have become deeply interwoven in various aspects of their life, from keeping in touch with their loved ones to doing their job more effectively. Despite the tremendous technological progress that has been made, and the value created for the average user, the general direction of the digital world has tended towards centralisation.

Unfortunately, most of our interactions online are now mediated by a handful of hyper-scale internet companies, which have massive growths in terms of user base and profits, made possible by the powerful economies of scale exhibited by online content aggregators[1]. The modus operandi of the most popular Internet companies is to offer free services to vast swaths of people who, through their usage, generate big amounts of data that can be monetised in various ways, including being sold to advertisers. This has led to the emergence of what Shoshana Zuboff refers to as “surveillance capitalism”[2], an economic model that relies on the intermediation and monitoring of online interactions and the media people consume; one that creates incentives that are fundamentally misaligned with the user.

The explosion in online services has created tremendous value for people, but at the same time it has led to an increasingly fragmented Internet. Users have to maintain a separate account for each of the service/platform they use, and companies have no incentives for opening up their platforms, leading to walled gardens and scattered digital identities. Seen through a simple consumer lens, this doesn’t look like a big problem; users have choice and they can stop using a specific service if they want too. But looking at the situation through a techno-evolutionary lens, we are forced to acknowledge the continuous digitalisation of the world around us, and the increasing importance of our digital identities. The data we create in these walled digital gardens are part of our digital identities, and there is no way to separate them. As this trend takes its course, our digital identities are becoming more important, and they act as gatekeepers to the digital world, yet, they are under the full control of the companies that provide them, with users having little recourse in case their accounts get compromised or closed.

The fragmentation of the Internet into islands of data that don’t have the ability to talk to each other also means that users and their data are “locked-in” into services with no easy way to switch, effectively constraining their digital sovereignty. Because of this asymmetry in power, companies have the ability to censor content or completely close accounts that they don’t agree with, without noticeable repercussions for themselves. In a world where competition is thriving and users don’t incur high switching costs, this wouldn’t be a problem, but that is not the world we live in, currently. Certain platforms service billions of users worldwide with little effective choice left for them, because of the powerful network effects exhibited by these platforms.

Governments around the world have adapted in various ways to the emergence of the networked society. Some, like China and Saudi Arabia, have seized the opportunity to reinforce their authority over people, and maintain political control. Western governments have had a dissonant approach at best, with efforts that range from spying on their citizens to legislation that tries to guarantee certain online rights. The Snowden leaks[3] showed that the western surveillance machine is far reaching, spanning many countries around the globe, and coerces some of the biggest tech companies in its pursue for data. On a more positive note, there are legislative efforts that are trying to offer more protection to end users, both from over encroaching spying by the government or from data abuses made by Internet service providers. One such effort is the GDPR[4] which is useful and could lead to positive change, but it is only slightly improving the status quo; laws such as the GDPR require service providers to offer certain guarantees regarding user’s data, but they will not lead to fundamental changes in the way people consume web applications or online content; the asymmetric power relationship between the company and the user will be similar. The same centralisation forces will remain in place and perhaps new ones created because of the cumbersome technical requirements imposed by the newly created laws. What’s clear is that the centralisation of the Internet into few large companies has created a choke point, one that can be targeted and subjugated by state actors, sometimes secretly, and without consent from their citizens[5].

We are left with a situation where our privacy is attacked from two different sides, albeit for different reasons: economic from one side, and political from the other. Privacy is an important requirement for the democratic process to work smoothly[6], and there are already examples where mass surveillance tools have been used to subvert it. What was once hailed as a great equaliser and beacon of freedom has been coerced into being a mass surveillance machine, one that we are increasingly dependent upon, but unfortunately, don’t have much control over.

Self-hosting - a way to decentralize the internet and attain digital sovereignty

The vast majority of web applications in use today use a model where the development and the hosting of the application is done by the same company. For example, Gmail, a very popular email application, is both developed and hosted by Google on their own hardware servers; when someone uses Gmail, they have to use a google owned identity and store all their data, in this case, emails, inside Google’s service.

In contrast, self-hosting means that instead of relying on a multitude of 3rd party web services, each with its own username/password and data silo, individuals and organisations would download and run applications themselves on their own personal server or servers(hardware). In this way, they would retain control over their own data and fundamentally change the relationship between themselves and the application creators. By not being able to leverage user data as a tool to monetise application development, a more direct monetisation model would need to be used, one that better aligns the incentives of the application developers with those of the users.

What are the requirements for self-hosting?

In order to be able to self-host Internet applications and have a good user experience, the following parts need to come together:

- Internet connected computer that is 24/7 online - this can be a VPS[7](virtual private server) rented from a hosting provider like DigitalOcean or a physical computer at home, connected to a reliable connection with a static IP, preferably running the GNU/Linux operating system.

- Self-hosting platform - software that runs on a computer that is always on and always connected to the Internet, that provides a way to install and manage applications. Protos is a software project that aims to fill this need, but there are other projects that have similar goals: Sandstorm, Urbit, Cloudron, etc.

- Domain name - a regular domain name part of the DNS[8] that is used to identify the users and applications that are running on the self-hosting platform. For example, a user can be identified as “user@domain.com,” and an application could be identified as “mail.domain.com”.

- Applications - applications that can be easily installed and used through the self-hosting platform. They are the end-goal, because, they provide the value to the user.

But the devil is in the details, and having all the required things by themselves does not make for a good self-hosting experience, one that can be approachable by average users without technical experience. It’s important how they come together, to become whole with a smooth user experience that hides the parts that create that experience as much as possible; just as you don’t notice what goes behind the scene to create and display your Facebook feed, installing and using an application on a self-hosting platform should be equally boring.

Self-hosting is not new, and organisations and technically inclined hobbyists have done it since the dawn of the Internet, but the usual way of doing it requires effort and deep technical knowledge. Take for example an email server: it requires knowledge on how to install Linux software from the command line, have thorough understanding of how the email protocols (SMTP, IMAP etc) work, and know how to configure a domain name. And many other server-focused applications pose similar challenges. But there is no fundamental reason why that should be the case, a view which is not held only by the Protos project, but increasingly reflected by the various self-hosting software projects that have been started to solve this problem: Sandstorm, Urbit, Cloudron, Cozy, Solid etc. It is becoming clear that the most important pieces of the puzzle that can tie everything together to deliver self-hosting into a product with mass appeal, is the self-hosting platform and a rich ecosystem of applications that can run on top of it.

Protos’ vision for self-hosting

Protos can be considered a new and 3rd category of (virtual) user devices, next to the smartphone and personal computer. This software can run on any computer that acts as a server (always on and always connected to the Internet, like a VPS[9] or low power computer at home) and becomes a personal and private “cloud” for the user, one that complements the users other devices just like current Internet services do. As with a smartphone or computer, a user can easily download, install, and run applications on the Protos self-hosting platform. But the type of applications that run on it differs from the ones running on smartphones or personal computers; they could be web applications that can be loaded via the browser, similar to a Google Docs document or a Trello board, but could also just be “server” type software that provides functionality to an application on the smartphone or personal computer, like an email server or VPN[10] server.

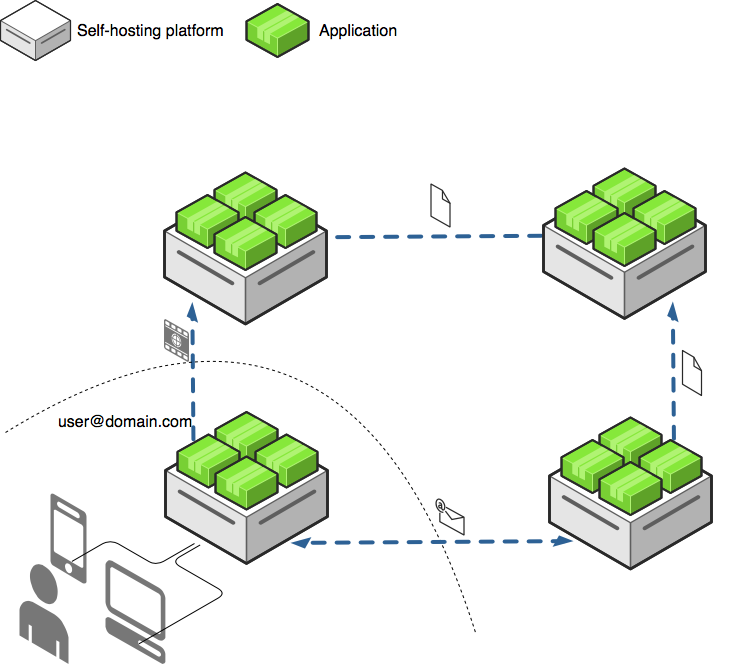

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Each Protos instance is identified by a domain name (e.g. domain.com), and can service one or more users, a user will be identified by his

Simple applications like Etherpad[12] are ideal to run on Protos, but it is expected that with a wider adoption of self-hosting platforms, more complex applications like p2p or federated social networks[13] will also become more popular, since it will be very easy to run them. For example, the oldest and most popular Internet communication application, email, is a federated protocol which works in a fully distributed way. Any user can run their own email server on their Protos instance, retaining full privacy and control over their data.

Figure 1 shows a typical scenario where a user’s devices interact with applications from his Protos instance, but some of those applications also interact with applications hosted on other Protos instances. Email, social networking, and any other type of application that involves user interactions across instances would work in a distributed way, like portrayed in Figure 1, by sending messages between each other, with no single instance having control over the whole system.

Challenges that are impeding the self-hosting vision

While self-hosting as a concept is straightforward, making it into a practical and mass-market product is not. There are practical challenges that need be overcome before the vision set forth in the previous section can be ready for a wider audience, and these challenges are mostly technical in nature: for various reasons, server software has evolved to be complex, hard to install and hard to manage but if self-hosting is to become mainstream, this complexity needs to be hidden and the experience needs to become more similar to the smartphone experience of installing and managing applications.

It all boils down to convenience, and how easily users can adopt and switch to using self-hosted applications, in contrast to using services like Gmail and Facebook that offer convenience but sacrifice privacy. While current self-hosting projects have made tremendous progress in lowering the barriers to self-hosting, a few more leaps in usability are required to reach a level where the technology is ready for non-technical people. And that is where the project’s effort will be focused, through the goals mentioned earlier.

The benefits and ramifications of self-hosting

Making self-hosting a viable alternative to centralised services will bring immediate tangible advantages to the people that adopt it, but there are potential long term benefits that can affect innovation in the digital world: governance or even democracy itself.

In the short term, using a self-hosting platform like Protos could confer a person the following benefits:

A single identity. The user’s identity would be stable over time, since it would be connected to a domain name that the user owns and controls.

Increased privacy. Since a user’s data would be under their own control, 3rd parties would not be able to access it without explicit sharing by the user.

More control and flexibility. The data and applications that are self-hosted can be easily backed-up and moved to a new hosting provider or an Internet connected computer at home.

In the grand scheme of things, a world in which more people used self-hosting platforms with strong security and cryptographic primitives would lead to a more geographically diverse and resilient Internet, but also, one that changes the dynamics of state-sponsored attacks on the Internet infrastructure. An Internet where communications are encrypted and have a diverse geographical distribution makes those kinds of attacks more difficult, and requires them to be more targeted. This doesn’t totally strip law enforcement of their tools to pursue criminal activity, but it makes it difficult for them to use the kind of mass surveillance tools revealed by the Snowden[14] leaks. Countries that keep a strong grip over the online behaviour of their populations would find it much more difficult to do so, and in tumultuous situations like uprisings or revolts against oppressive governments, people would have much more resilient tools to coordinate with.

Another potential outcome of a more decentralised world where users are not locked out of their own data is more innovation at the application level, because of lower switching costs between applications. If someone installs an application on his Protos instance, the data created by that application will be under his control; if a new, better application that understands the same data format appears, that person will be able to install it and import the data from the old application without being forced to continue using the old one. That plus-extensible protocol can act as a catalyst for innovation, eliminating the ability for gatekeepers to form around successful communities. Imagine if Facebook or Twitter would be interoperable, or if 3rd party clients could be possible; most likely, it would lead to more competition and better outcomes for the users.

Last but not least, self-hosting can act as a bridge to the exciting and experimental world of public blockchains[15]. The publication of the Bitcoin whitepaper in late 2008, and the following release of the Bitcoin software, was a defining moment in the history of the Internet, it proved that it is possible to create digital value tokens in a fully decentralised way and without a central authority. That inspired a whole range of wild but promising projects, which, through the power of peer-2-peer digital consensus, try to revolutionize various fields, with examples such as governance[16], currency issuing[17] and media streaming[18]. Most of these projects are based on peer-2-peer software that benefits from being online 24/7, and requires considerable resources to run, which means that running them on a smartphone or laptop would be difficult. On the other hand, self-hosting platforms like Protos are the ideal place to run this kind of software projects because of their always-on/always-online nature, and this could be a new avenue for delivering such projects to a wider and more diverse audience, without repeating history and relying on 3rd party providers susceptible to the forces of centralisation. Running a Bitcoin node or a similar blockchain project would be transformed from an endeavour that requires deep technical knowledge, to one that requires only an economic commitment (the cost of online hosting).

In a world that is increasingly dependent on digital infrastructure, maintaining our digital sovereignty is more important than ever, and to that avail, one of the best tools we have is self-hosting.

Addendum

Why do servers need to be always on?

Most of our online interactions are asynchronous, which means that most Internet applications require always-on software servers[19] to mediate these interactions. To illustrate this the following e-mail scenario is given, although the same pattern applies to other time of online interactions:

When Alice(alice@gmail.com) sends an email to Bob(bob@yahoo.com), Alice’s email client transmits the email first to the email server[20] that represents gmail.com. Once gmail.com’s email server has the email, it will attempt to deliver the email to yahoo.com’s email server. If all goes well, the next time Bob’s email client goes online and retrieves it’s email from yahoo.com’s email server, it will see the new email from Alice. This explanation simplifies the actual process to some degree, but it’s accurate enough to illustrate that in order for Bob to be able to receive an email when his computer or smartphone is not online, he needs an email server that is always online to accept the email on his behalf.

What facilitated the centralisation of the Internet?

It is important to understand the forces that lead to centralisation, because, those also made Internet applications more accessible to the masses, so, potential solutions will have to take that into account. There are a multitude of reasons for why the Internet became more centralised, but there were a couple of major forces that contributed; economic forces driven be economies of scale, which in turn were facilitated by technological innovations in the way software is developed and delivered.

The economic forces are more obvious and have been touched upon, earlier in this text. It started with the commercialisation of the Internet, and the modus operandi remains the same; companies seek to gain a market advantage by attracting masses of users and then, locking them on their platforms through various means: Microsoft did it by bundling IE with Windows, and implementing proprietary plugins for it; Facebook does it by creating a network effect among its users and the content they generate on its platform, without being interoperable to other social networks; and Google does it by slowly re-producing functionality offered by other popular services (or acquiring them), so that users don’t have to go outside of its ecosystem. The pattern is always similar, and perhaps this shouldn’t surprise us; companies benefit from economies of scale and market monopolies, and it is no surprise they tend to gravitate towards that. This is not a fundamental problem as long as there is healthy competition in the market, but the problem is that currently, we are in a situation where the Internet is dominated by a handful of global players which have near monopolies in their segments of activity.

While companies tend to want to grow as big and as fast as possible, they can only do that as fast they can acquire customers or revenue. In the first stages of the personal computing revolution, software was shipped to the user using portable storage media like CD’s, and increasingly, over the Internet, once it became more popular. The user had to actively be part in the software supply chain by first acquiring it, and then installing it on the operating system running on their computer. This meant that considerable effort and knowledge was required of the user, to install and keep software updated; and since each piece of software had to be compiled for a specific operating system, it took considerable effort for developers to target multiple platforms; both of these constraints limited the total addressable market of software.

1995 was the year that marked the start of a new Internet and computing era, because, JavaScript was introduced by Netscape; JavaScript allowed developers to ship code with every web page, code that could interactively modify that web page based on input from the user, or data from the web server. Developers were no longer limited to slow static websites that had to be updated on the server, but could now create interactive applications right in the browser; applications that would act and feel similarly to normal desktop graphical applications. (While there have been several in-browser multimedia content technologies like Flash or ActiveX, JavaScript has now prevailed in terms of browser and developer mindset, and is used in the vast majority of web applications). This technology was crucial, because, it changed the software supply chain by eliminating the user from the installation equation, and allowed developers to, more or less, target multiple platforms. To take Gmail as an example, a web application with over 1 billion monthly active users, a user only needs to visit its website at https://mail.google.com using a web browser, and the latest version of the application will load and become usable in a matter of seconds, without any help or knowledge from the user. At the same time, Gmail developers can continuously develop the application and push updates as soon as they are ready.

The leap in efficiency in this way of creating and delivering software cannot be overstated, and it enabled some of the hyper-scale Internet companies like Google or Facebook to acquire large amounts of users in relatively few years. The importance of a smooth application delivery model seems obvious now, and it has been repeated in a second computing revolution, the smartphone revolution. Android and iOS, the dominant smartphone ecosystems, have application stores that are similarly smooth when it comes to delivering applications to the user. You can install and start using an application in seconds, and they are kept up to date without requiring any effort from the user. But there is a fundamental difference between the smartphone application stores and the Web: the former are closed platforms while the latter is an open platform. This shows that a platform’s success is conditioned in large part by how easy it is for a user to plug in on that platform and gain value.

[1] “The Bill Gates Line – Stratechery by Ben Thompson.” 23 May. 2018, http://stratechery.com/2018/the-bill-gates-line/

[2] “Big Other: Surveillance Capitalism and the Prospects … - SSRN papers.” 17 Apr. 2015, https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2594754

[3] “Edward Snowden - Wikipedia.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Snowden

[4] “General Data Protection Regulation ….” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/General_Data_Protection_Regulation

[5] “List of government mass surveillance projects - Wikipedia.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_government_mass_surveillance_projects

[6] “How Much Surveillance Can Democracy Withstand? - GNU.org.” https://www.gnu.org/philosophy/surveillance-vs-democracy.html

[7] “Virtual private server - Wikipedia.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virtual_private_server

[8] “Domain Name System - Wikipedia.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Domain_Name_System

[9] “Virtual private server - Wikipedia.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virtual_private_server

[10] “Virtual private network - Wikipedia.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virtual_private_network

[11] “Who owns your domain name? - IWantMyName.” 8 Dec. 2015, https://iwantmyname.com/blog/who-owns-your-domain

[12] “Etherpad.org.” http://etherpad.org/

[13] “Giving social networking back to you - The Mastodon Project.” https://joinmastodon.org/

[14] “Edward Snowden - Wikipedia.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Snowden

[15] “Blockchain - Wikipedia.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blockchain

[16] “Democracy Earth.” https://www.democracy.earth/

[17] “MakerDAO - Stability for the blockchain.” https://makerdao.com/

[18] “LBRY - Content Freedom.” https://lbry.io/

[19] “Server (computing) - Wikipedia.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Server_(computing)

[20] “What is an Email Server (MTA)? - Definition from Techopedia.” https://www.techopedia.com/definition/1660/email-server-email